Whilst at Stowe, Marc Koska OBE (Bruce 79) was described as someone who rebelled against the system and he himself admits that he didn’t discover his true purpose until he left School. All he did know was that his purpose was to make a difference. Stowe allowed Marc to be part of a wonderful community where he felt nurtured and supported, which gave him the confidence to know he could achieve whatever he wanted to.

What he didn’t want to do was follow the crowd and take small steps forward, he wanted to do things on a large scale and challenge the status quo by pushing boundaries – another trait that Stowe nurtured and encouraged.

The ten years after leaving Stowe saw Marc travelling the world and living in the Caribbean making models of scenes of crimes to be used in court. During this period, he ‘dabbled’ in city life but quickly realised the commercial route was not for him. His passion was in health care but he didn’t know how or where he fit in. Then, in the mid-80s, came the rise in the transmission of HIV with TV adverts showing tombstones and the words “loved ones will die of HIV”.

This was a major turning point for Marc, who couldn’t understand why there wasn’t anything that could be done to stop the rising rates of transmission. It had already been reported in the newspaper that the main reason was down to the re-use of syringes – something that was only meant to be used once was being used 3-4 times by different people. Of all the cases of HIV and Hepatitis in the world, the syringe was the main cause. What followed reading this news was three years of research for Marc, trying to figure out what he could do.

With 50 billion syringes manufactured each year, even the smallest change would be a huge adjustment and a vast difference in cost. Knowing this showed Marc that if he was going to make a difference he needed to understand every aspect of syringe manufacturing in order to come up with a different design. He quickly established that it was all about money and manufacturing technique, so, he had to find a way to altar the process in order to make the syringe act differently at the same time as not adding to the cost. He also realised that his mission was seen as a ‘do-good’ project, the fact that a change in the system would result in a product which would stop the rate of transmission and save lives was inconsequential. Industry and health policy do not go hand in hand. Therefore, he had to come up with a commercially viable solution to try and help. Seventeen years later, the K1 single-use syringe design went into production with over 10 billion, and counting, being sold worldwide to organisations like UNICEF and national governments.

With 50 billion syringes manufactured each year, even the smallest change would be a huge adjustment and a vast difference in cost. Knowing this showed Marc that if he was going to make a difference he needed to understand every aspect of syringe manufacturing in order to come up with a different design. He quickly established that it was all about money and manufacturing technique, so, he had to find a way to altar the process in order to make the syringe act differently at the same time as not adding to the cost. He also realised that his mission was seen as a ‘do-good’ project, the fact that a change in the system would result in a product which would stop the rate of transmission and save lives was inconsequential. Industry and health policy do not go hand in hand. Therefore, he had to come up with a commercially viable solution to try and help. Seventeen years later, the K1 single-use syringe design went into production with over 10 billion, and counting, being sold worldwide to organisations like UNICEF and national governments.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) credits around several hundred thousand lives being saved directly due to the K1 auto-disable syringe. Alongside the lives saved directly, there are millions more who have been saved through the prevention of chronic infections. Most notably, Hepatitis B. No matter where you are in the world, treating Hepatitis B costs $10,000, it is a slow killer and diagnosis was considered a death sentence. The most common cause of Hep B? Shared syringe usage.

In 2005, Marc and his assistant set up the SafePoint Trust as a way of lobbying, with integrity and honesty, to push the Government and WHO to declare better legislation and policy in the future of syringe usage. A few years after this campaign began, the WHO declared a global policy that by 2020 all syringes would be auto-disable, a class of product which cannot be re-used. SafePoint were the founding member and the accelerator that pushed the policy through.

Years before the term Covid-19 even existed, Marc found himself thinking about what his next steps would be for the K1 auto-disable syringe. After the patent had expired there would be no commercial gain so he couldn’t run it as an organisation but felt there was more to be done. Over the years, whilst travelling the world, Marc had compiled a long list of issues and problems he could see with health care systems and could categorise the majority as ‘access issues’.

For example, if there was a flood in a small town that caused a bridge to collapse and be swept away and there was a woman in labour on one side and a doctor with medical supplies on the other – how would the critical vaccinations be able to reach the soon-to-be mother and new born? No matter how this situation was looked at, with current offerings, there was no way of solving it.

Then, one day, Marc was sat in his garden when a bee flew past and an idea came to him – you could mimic the way that nature and bees have evolved to give stings effectively to their enemies. Looking at the list of issues previously identified, it became apparent that all of them would either be solved or benefit immensely from this train of thought. The next step was working out how to make this idea a reality. Much like a jigsaw puzzle, Marc had most of the pieces, he just needed to find out how to put them all together and find the correct solution.

One thing Marc was sure of was the name, ApiJect, which came from the Latin ‘apis’ for bee and ‘iactare’ for to throw, which was the closest translation for bee sting.

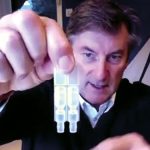

The concept and manufacturing techniques that would allow ApiJect to go into production already existed, were well-known and already well respected around the world. One, the needle, which is still the most common way of delivering medicine into the body (and will remain the most common despite the advances of other methods) and secondly, the plastic blister. All that was required was to figure out how the two could fit together. At first this seemed like a simple concept but it was harder than anticipated and took a team of five two and a half years to solve.

In order to be able to make the next leap forward, Marc partnered with Jay Walker, an American known for starting Priceline. They were at a WHO conference in Kazakhstan with a large US contingent of 4* Generals, all of whom were in primary health care when the true potential of ApiJect became clear. One of them saw the prototype and claimed it was exactly what the strategic national stockpile needed. The current American stockpile for bio-terrorism and natural disasters compiles 8bn dollars’ worth of drugs but has no way of getting them out to people other than the traditional methods. In addition to this, there is no surplus of delivery products or methodologies available, meaning that if the world makes 50 billion syringes a year but needs 10 billion more, the only place to get them from is the existing supply line.

Rolling forward a few years to 2020 and we find ourselves in the middle of a global pandemic and a situation where getting access to a vaccination is a critical issue. How do we access the care workers, how do we reach the vulnerable and how can we deliver the vaccination safely and record who has received it? ApiJect is able to fill the role in answering all these questions, especially as it has become clear that a key part of treating Covid-19 will not be able to take place in a centralised or localised location due to not being able to gather such large numbers of people together. Transportation services such as FedEx, UPS and Amazon are going to be key when it comes to the distribution of the vaccination.

So, what is the role that ApiJect fills? They are the ‘fill and finish’ aspect of the process, they fill the device, close it and finish it by labelling, adding an RFID tag, including a particular style of needle, adding a cap and packaging it all into a box. Working with Operation Warp Speed they are making huge progress and are going to be a major force in delivering the vaccination or therapeutic. ApiJect works by having a plastic blister, made of low-density polyethylene, with exactly 1/2ml of liquid (the same size as any vaccination), a cap is then added to this to which creates a water seal and then the needle screws into the cap. By squeezing the blister, the air compression drives the liquid into the body – in total, the process takes around five seconds. It is also quick to manufacture with 25 units being made, filled, serialised and closed every three seconds. That equates to 200 million doses a year per machine. In ten months time they are opening a factory which will have 15 lines. The real advantage of this is that each element can be varied slightly to fit any vaccine or therapeutic. ApiJect is working alongside the Health and Human Services department in the US and are involved with the military who are helping to build and defend the infrastructure that is being put in as they are now a National Security Asset for the United States.

When asked what he thought about the origins of the virus and how he saw the future, he answered that he had to view it as natural evolution caused by the imbalance of eating and interacting with wild animals. “Humans are in a poor state to be dealing with that, we no longer live in caves or eat raw meat, we just don’t have the natural defences. We have evolved away from the dangers of the natural world so when we do come across one, it takes advantage! It is going to be something that we have to adapt to as we won’t be able to eradicate it entirely, in the meantime what we have to do is come together and learn how to protect our loved ones and the vulnerable.”

In regards to the future, he is acutely aware of the demand for vaccinations and therapeutics. A set number of vials containing the drugs are being made and a set number of syringes are being made, even though demand is going up, there aren’t any new factories being built to accommodate this. Why? The answer simply is cost. Since Covid-19, no new factories have or are being built in order to supply more vials or syringes, the amount it would cost to build just for a vaccine to come and eradicate the virus in three years doesn’t make financial sense. So, in the meantime the displacement from existing supply lines over the last few decades into the possible Covid-19 treatment system causes a void. It has been estimated that thousands of children are suffering and dying daily around the world due to not receiving childhood immunisations, a system that has taken decades to build in order to deliver to the younger generation has been destroyed. There really is an enhanced urgency for primary health treatment around the world, which is something that ApiJect can help with.

If there was any advice Marc could give the children of today it would be to find out everything they can about Covid-19 and ensure they have as much knowledge as possible. This is the first pandemic that has existed at the same time as social media, now more than ever, it is important to be able to distinguish fact from fiction regardless of who is saying it. This is likely to dominate the next ten years of people’s lives so we should all look out, observe, listen and acknowledge when the answers aren’t there and do something about finding them.