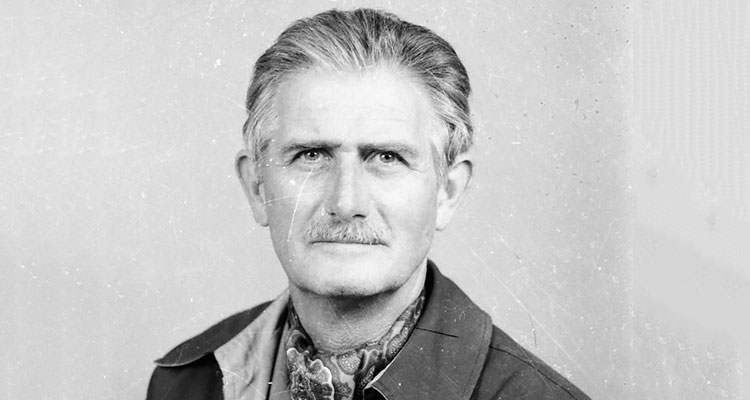

02 January 1929 – 20 April 2017

Jeremy was one of the last of a breed of men to be sent from England to settle in Africa. The political map of Africa in 1948 still showed an almost unbroken pink strip from south to north.

He was the eldest son of Doctor Eric William Winch FRCS. Jeremy and his brother, George, attended Stowe during and just after the Second World War. Jeremy was not an academic success perhaps due to his surviving meningitis aged 13. The school nurse acted with the greatest speed correctly identifying the meningitis, isolating him and reporting the fact to the Headmaster. Penicillin was not widely used, there was no NHS so most medical treatment was private and meningitis was an untreatable killer. My father was to all intents and purpose, dead. A risky operation saved his life: two holes were drilled into the top of his skull and penicillin was applied directly onto the meninges. My father survived and came out of his coma a week later but understandably had a very long recovery period.

He loved Stowe, as he recalled “a rather shabby stately home, cold and damp with a smattering of boys. Not the grandeur of the place as it is now.”

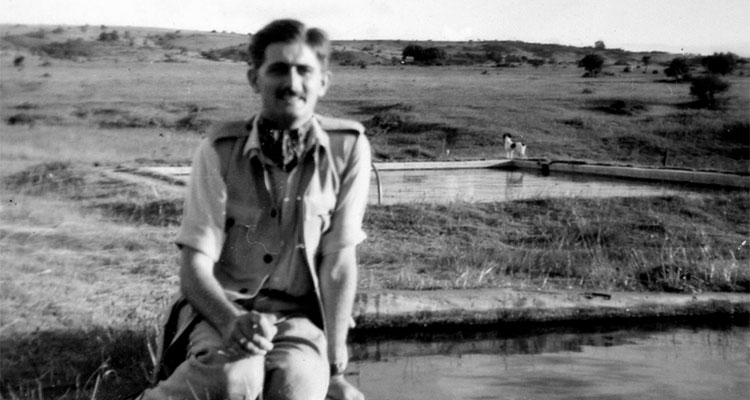

He left Stowe having scraped his School Certificate. His academic achievement and health meant that he was excused war service, something that bitterly disappointed him. Instead, he was sent to central Africa by his father. Jeremy sailed via Suez to Beira in Mozambique and then the train up to Southern Rhodesia to start life as an apprentice tobacco farmer for Winston Field out at Trelawney in Mashonaland aged 18. He was in awe that Rhodesia Railways not only had no food rationing restrictions but also served coffee.

He was collected by truck from Salisbury station and after just one night was taken the 120 miles out into the bush to start his apprenticeship. His first task was to clear virgin bush ready for the next season’s tobacco crop. It was a tough and punishing first year.

After several years hard labour and the wish for a change, he found his metier in compulsory military service that all colonials were obliged to do. Serving in the militia, he was offered regular service in the Staff Corps and so began a 35 year career in the military. The Staff Corps was the core element of the Federations’ Army. In 1956, he was posted to Bulawayo where he spent most of his military career. As Federation failed and the Army reorganised, he was variously a Staff Corps Military Policeman, a Rhodesia Regiment drill and weapons training instructor and RAR Warrant Officer. His efforts during this period kept many young men alive in the conflict that ensued. In the 1960s his idea of a good weekend would be to explore forts of Rhodes’s pioneer and relief columns, long forgotten and deep in the thorn bush. He would return from a prospecting weekend bloodied and torn by thorn bushes flushed with the success of finding a military tunic button, an old whisky bottle (there were lots of those!) or empty cartridge cases, lots of them too. All were historical finds that contributed to his retinue of stories. Exploring the ancient stone structures of Zimbabwe was of equal interest to him. He was an early explorer of great Zimbabwe as well as the numerous smaller ruins in and around the Matabeleland. Shortly after independence and during the integration phase that followed, Jeremy’s career came to an abrupt but natural end.

He retired to his smallholding out towards Esigodini with Fiona and their family where they lived almost self-sufficiently through the 1980s and 90s. In his declining years, he devoted himself to his original passion that was all things military and historical. His collection of Winchester repeating rifles was one of the few complete collections in the world and included the rare Golden Boy. He was an avid collector and preserver of military history, and presented a weekly programme on RBC using items from his collections as props. He was an authority on the Boer wars and was particularly knowledgeable on the peripheral outcome of that conflict upon Southern Rhodesia. His collection of Brittan’s original lead soldiers that he started collecting as a boy, many still in their original box sets, was large and rare. His expertise and knowledge in this area was widely acknowledged.

Throughout his life he never forgot, nor let his family forget, that he was a Stoic. He was an avid reader of the School magazine and kept in touch with both School and Old Stoics. His last visit to Stowe was in 2004/5 when he was confined to a wheelchair. Stowe made a great fuss over him which he revelled in. When he returned to his oldest son’s cottage in Banbury, with eyes lit up from a wonderful day out he said that the School was never as swish as it is now and how wonderful the pupils were. He had been royally treated by the School he loved.

He died shortly after his second wife who died suddenly in 2016. He is survived by two sons, Dan and Nicholas, from his first marriage and Georgina, Vivien and James from his second.

Dan Skipworth-Michel