Rupert Douglas-Bate (Temple 82)

A vexed young man once asked his parents to give him a powerful motorbike for his 18th birthday. They were horrified, but the young chap kept pestering until finally, they agreed – subject to conditions. The first was the young man would do a bike mechanics course, taking several months, then he would submit to several more months of standard bike lessons with advanced lessons added on. Finally, the young man would agree to do all this with his Dad, who would roll up his sleeves and get stuck in with him.

This is a true story; however, I cannot remember which of my business associates told it to me. What I do know is the Dad turned up and the young man played his part and turned out to be a superb motorbike rider. Further, the relationship with his parents, notably his father, was deeply enhanced by the whole experience and his mother’s waking nightmares of visiting her son in a spinal ward dissipated like the mist on a summer’s morning.

It is a deep honour to be asked as an Old Stoic to write the leading article on ‘Sustainability’ for The Corinthian. It is a subject, which as a capitalist and as a humanitarian development worker, is close to my heart. When I was thinking about how to approach the matter, I realised it would be helpful to define what sustainability means, at least for this article, as it is a word bandied around so much with shades of meaning. I slept on it and at midnight the word “safety” came to mind, so I think I’ll stick with that.

The world certainly feels like a dangerous place at the moment. In 2010 the ‘Doomsday Clock’, which is the predictor of global catastrophe run by scientists in Washington, stated the catastrophe was at ‘6 minutes to midnight’. Since then we have steadily ticked closer and today, in 2020, we are ‘100 seconds to midnight’, with the Doomsday people citing “risks such as worsening nuclear threats, a lack of climate action and the rise of cyber-enabled disinformation campaigns that undermine society’s ability to act”. Then, of course, there is Covid-19.

How should this rather gloomy world scenario affect us? After all, we may feel like ants, small and invisible in a sea of grass, with giants who represent problems in the world occasionally juddering in the background and missing us – we hope. Is it possible that the problems in today’s world may cause a similar sense of visceral fear of potential loss that the parents of the young man felt? Yet I ask myself, and you: Can we be inspired by how they successfully responded to his demands for a motorbike?

It feels to me highly likely that these parents analysed the problem and the fears associated with it and, in doing so, faced the facts square on. They listened carefully and together, with their son, built a new and better reality in partnership with him and not despite him.

Was their fear therefore, a bad thing? Here, I propose not, it was a very healthy fear. But more than that, it was followed up by action and respect for their son, which became mutual. In the search for safety, a bit of fear – call it respect – can be extraordinarily helpful. Imagine trying to cross a road without a bit of fear. Furthermore, this small fear actually gives us freedom. When we do decide to drive on the correct side of the road (and not die) we can go on almost any road on the map, the world opens up. Sustainability is everywhere.

So, the world faces momentous problems; a lack of climate change action, dictatorial regimes (some of whom deliberately cause refugee crises and most of whom crush their people), then there is Covid-19, fake news and cyber-attacks to top it off. How can we face these problems? Should we bother? Is it worth the hassle?

My sense is that just as these parents responsibly engaged with their son out of a little bit of fear, we too must respond and become engaged with our planet and the people on it who live in something more like a sea of fear. From my work overseas, I know the poor arise in the morning and often the first exam to pass is finding breakfast for their children or parents. The same cortisol chemicals flood the bloodstream as when we sit down to an exam or go for a job interview. Every day is exam day for the poor.

Today, according to the World Bank, there are over 620 million youth who are not in employment, education or training (NEET) across the planet. At the same time, the United Nations International Labour Organisation reports that the two main determinants of social unrest are unemployment and poor economic growth.

This fear is why we see small boats of refugees trying to come here across the Channel. In 2011 we saw the summer riots in the UK, after which one youth rioter said: “All I can tell you is that me, myself and the group I was in, none of us have got jobs. I’ve been out of work now for coming up to two years, 18 months…. look this is what’s gonna happen if there’s no jobs offered to us out there…”.

We are not going so solve all the world’s problems in a day, but we can tweak the course of history. Small gestures, especially kind ones, can make a big difference and more so when they are on target. I believe capitalism with a human face is a vital part of the answer to calm global violence, which is why I have started my second NGO, Global MapAid, to show where there are gaps in training and support for small business start-ups and small business expansions.

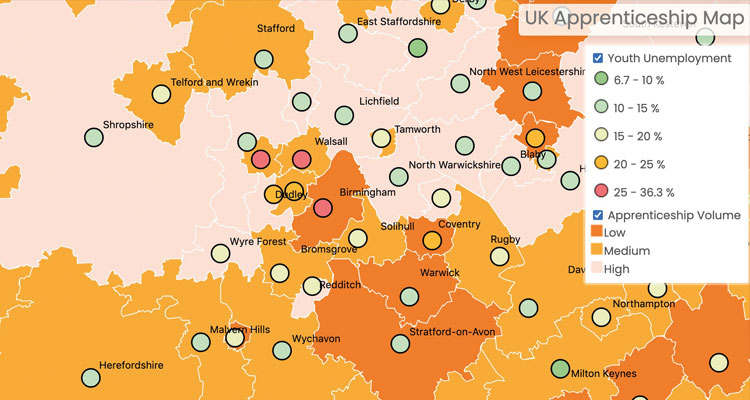

We make maps and visuals to show policy makers where to focus their efforts and unemployed people where support may be more accessible.

But NGOs and small-time capitalists like me are not nearly enough. The Times published an article in May 2019 entitled: ‘Charity Begins at Home for the Richest 1,000’, stating the overwhelming majority of Britain’s richest 1,000 people gave away less than 1% of their wealth in 2018 and only one in ten of the UK’s richest 18,000 people, those worth £10 million or more, donated anything to charity at all.

There is a vital role to play by the world’s very wealthy people to help the world become a safer place, but they must step up to the plate and be counted and not assume that because they have so much, they are safe. They are not. We are all in this together. As Monsieur Macron remarked to the US Congress in 2018: “There is no Planet B”.

Rupert Douglas-Bate (Temple 82), lives in sin near Henley-on-Thames, with his fiancée Nathalie Houdret. They have been happily trying to get officially married, but Covid-19 keeps getting in the way. He also runs his not-for-profit Global MapAid and his business, Smile Food.