Based upon the unreliable memoirs of Joel Corrigan (Lyttelton 87).

A Prelude to Misery

“The darkness was complete; I could hear the others ahead of me but couldn’t shout for fear of getting caught: I had no choice but to continue crawling as I didn’t want to be left behind. I kept bumping my head on the ceiling but the presence of the hand-sized spiders that I’d spotted before the torch died seemed to overshadow the pain. I thumped the damned lamp repeatedly but it refused to come back to life. My knees were throbbing; the blackness seemed suffocating and I was close to panic. Why had I ever agreed to this…?”

This first experience of the underworld was when I was six years old and that adventure took place beneath the floorboards in my neighbour’s house. As usual, it was my older sister who’d convinced me that it was a good idea and we’d teamed up with the lads from next door. As was to be expected, we all got caught by their parents: the boys received a thrashing and had their mouths washed out with soap, whereas our folks just laughed. Maybe if we’d been punished back then my life would have taken a different turn?

In the years to come, Stowe nurtured my spirit of adventure by providing fantastic opportunities within the Caving and Climbing Club, Sub Aqua Society and the CCF, not to mention the hundreds of acres of what is essentially an adventure playground that would put Hogwarts to shame. In true Harry Potter style, I became obsessed with the legends of the tunnels beneath the School that had allegedly been used by the Hellfire Club in the 1800s and put enormous effort into uncovering their secrets during my 5 year incarceration.

I first ventured into a real cave when I was thirteen as part of a school trip and was instantly hooked. Caving is without a doubt the least glamorous of the adventure ‘sports’; it’s difficult to explain the fascination to normal people and mostly I don’t even try. A lot of the time you’re wet, cold, tired and miserable but the sense of achievement can be intense.

The years passed and I became more and more dedicated to caving. I joined expeditions and was fortunate to travel all over the world in search of undiscovered caves as the lure of original exploration is addictive. In 1999, I was invited to join a project in the Dachstein region of the Austrian Alps and this would come to dominate my life.

A Short Glossary of Terms

- Cave: Latin for ‘Beware’ or a hole in the ground that any sensible person would avoid.

- Choke: A collapsed section of cave. Can be a teeny bit dangerous and quite often will be rather snug.

- Confluence: The meeting of two or more rivers. As caves are (mostly) formed by water the term is used to describe a meeting point of multiple passages.

- Dachstein: A 3,000m high mountain range in the Austrian Alps.

- Dive line: a thin (2mm or similar) cord that the lead cave diver lays along the passage primarily to allow the explorers to return without getting lost should visibility be reduced. Losing the line can be troublesome.

- Draught/Wind: A good indication of undiscovered cave as it suggests a pressure change and/or a higher or lower entrance.

- Drysuit: A diving suit that (in theory) keeps the wearer dry due to the combination of water tight seals around the extremities and injected gas to provide positive pressure. Not always successful.

- Pitch: A vertical descent in a cave that needs to be equipped with ropes. Potentially hazardous.

- Pothole or Pot: A vertical cave.

- Rebreather: Home-made (in this case) breathing apparatus that extends the duration of time that can be spent underwater by recirculating expired gas that is then re-metabolised via some sort of science or witchcraft.

- Squeeze or Crawl: An obstacle that allows smaller people to laugh at the larger ones.

- Sump: A flooded section of cave. The least pleasant and most troublesome of all cave obstacles.

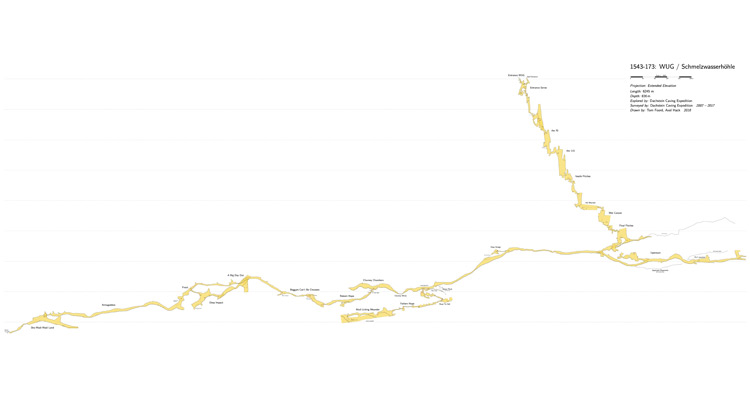

- Surveying: The painstaking and chilly chore of mapping discoveries using a combination of compass for direction, clinometer for angles, and tape for distance. The results are exported to a computer and some sort of wizardry helps the intellectual types to create a map.

- Underwater choke: A boulder collapse in a sump that can ruin your day if you’re not paying attention.

The Beginning of an Obsession: 1999

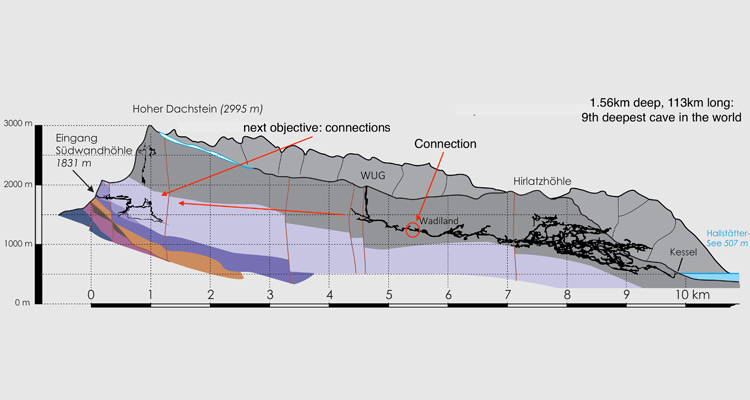

The Dachstein is the jewel in the crown of the Austrian Alps and from hundreds of miles away the eye is drawn to the jagged 3,000m high peaks and stunning glaciers. What casual observers don’t realise is that it is also the home to some of the deepest and longest caves in the world and the potential to extend these is what makes it a major target for explorers.

In the caving game, the region has something of a reputation for hard caves: bitterly cold (1-2°c), sharp, tight, flood prone and generally unforgiving. It sounds like the stuff of nightmares and in some ways that’s absolutely true, but for capable and experienced cavers these are all part of the challenge.

The raison d’être for the project is this: many years previously, the Austrians had discovered a huge, ancient cave inside the Hirlatz Mountain which was eventually explored for more than 100km distance and 1.1km depth (to put that into perspective the deepest cave in the UK is 300m). Exploration was stalled when they reached a huge chamber with a lake at the far end that disappeared into the unknown. This was now the realm of cave divers and there are very few people that could or would explore such a remote location. Back in the 1960s, a team of British cavers visited the area realised the massive depth potential, sought permission from the Austrian caving federation to begin exploration and were granted approval. For the next 30 years each summer the Brits searched the high mountains above the Hirlatzhöhle for cave entrances in the hope of discovering one that would lead down into the depths and connect to the main cave.

By the time I got involved, there had been three decades-worth of research and some very significant caves had been explored but the caving equivalent of the Holy Grail still eluded them. So, this is a story of two distinct halves: winter trips to the Hirlatzhöhle and summer trips on the mountains above with a rather complex timeline of events joining the two together.

After my first trip in 1999, I became the organiser and for the next ten years we explored some real brutes but none of these reached the Hirlatzhöhle. It was sort of like stabbing a pin into a gigantic pin cushion in the hope of finding a specific void far below, each pin representing a vertical cave that might take us several years to explore. The chances of success really were one in a million and it’s fair to say that I was slowly becoming convinced that it would never happen… Then in 2008, we chanced upon a small, insignificant entrance at 2000m altitude that was to be a game-changer: WUG Pot.

A Decade in the Hirlatzhöhle: 2005 – 2015

Each winter since the end of the nineties, a small group of us had been exploring the further reaches of the Hirlatzhöhle itself as safety required that we only attempt this whilst the mountains were frozen to reduce the risk of flooding underground. Our trips involved spending a week or more living in the cave as the limit of exploration was such a long way from the surface. Our main lead was in the far west where two of us were diving and exploring the tunnels beyond.

“The large passage continued on ahead of me into the unknown but our thin dive line took a sharp right hand turn and headed upwards into the boulder choke, which was the final significant obstacle of the underwater phase. Following this now required more care and attention as the cave dimensions went from a spacious 10m diameter to body-sized and any sudden move could dislodge the silt, which would lead to instant black-out conditions in the narrow and loose confines of the choke. Slow and deliberate was the order of the day: vent gas from the rebreather, vent gas from the drysuit, remember to exhale on the ascent so as not to damage my lungs, try not to touch the walls, do not let go of the line or all will be lost. After a few minutes of this, I was free and saw the bubbles break on the surface of the lake. I had arrived in Wadiland at the far end of the Hirlatzhöhle and the Stygian gloom of the huge cavern threatened to overwhelm me.”

Cave diving is one of the least pleasant activities at the best of times but when the water is 2°c and the dive base is about ten to twelve hours from daylight it is downright miserable. Over the next ten winters (from 2005 to 2015) we drove the thousand miles to Austria, carried absurdly heavy back packs up the mountain and to the far end of the cave and, continued our exploration beyond the flooded passages. We had many adventures and finally discovered a truly massive tunnel that we named Austrian Airspace, which was seventy metres wide with holes coming in from way above. This was a major confluence and we were certain that these inlets must come from some of the caves high up on the mountains but reaching and exploring them was going to take us many more years. Then frustratingly and without any warning, my long-term diving partner retired: this was a major blow to my morale and within a year this part of the project fizzled out.

Mountain Madness 2008-2018

The summer trips high up in the mountains continued year after year and attention focused upon the small, insignificant entrance we’d discovered in 2008. WUG Pot (standing for ‘Wot You Got’ Pot which is something of an in-joke and not suitable for public consumption!) had rapidly been explored down a series of magnificent pitches to a depth of 600m (experienced cavers would take about eight hours to abseil to this depth and maybe twelve or more hours to ascend). From the point where we leave the ropes behind, the cave becomes more horizontal in nature and big boreholes of 10m plus diameter are the norm. A kilometre or so further – with a height loss of another one hundred and fifty metres – the permanent camp is reached at -750 metres depth. The main way on (in geological terms) terminated around the corner in a boulder collapse. These can be troublesome obstacles that require the intrepid explorers to remove blocks (Jenga-style) to make progress without causing collapse. The wind blowing through here convinced us that we were heading in the right direction so we had no choice but to continue. Over a three-day period we dug and mined our way through this rock and mud-choked passage using crowbars, hammers, chisels, and gunpowder cartridges that we used to shatter boulders.

Eventually our efforts paid off and the squeeze opened up into a large chamber. Heartbreakingly, though, this tunnel ended after a few hundred metres and we lost the main way on, even though we knew the wind was coming from somewhere significant. It was to take us another eight years of hard labour before we got back on track…

During a re-survey trip into this part of the cave in 2016, the team felt a cold draught upon their faces and followed it into a squalid undercut. Continuing further, they reached a squeeze down into boulders with a very strong wind blowing towards them. This was it: ‘It’s not ideal’ was the missing link that we’d been hunting for years. Subsequent trips passed this obstacle to reach more huge tubes and the limit of the 2016 expedition was a large rock and mud wall with a passageway above heading off into the unknown. We made an attempt to climb it but the quality of the rock was very poor which made it far too dangerous without more equipment. A rethink was required.

2017 saw a very motivated crew on the mountain and we tackled the unclimbed wall down WUG Pot with renewed vigour. Using a combination of aid climbing (drilling and bolting our way up the rock) and winter climbing techniques (using axes and crampons) we got to the top and fixed ropes. More huge tunnels, climbs and descents took us farther and deeper until we again ran out of time and had to pack up for another year. In 2018, our decades of effort finally paid off…

Half a Century of Exploration

“I popped out of the small side passage into the mother of all chambers: 70m wide and maybe 50m high with the ceiling and walls well beyond the range of our lamps. My main role at this stage was to try to recognise this tunnel as we believed (or hoped) that it must be Austrian Airspace, the western-most limit of the Hirlatzhöhle that I’d discovered beyond the sumps almost a decade earlier. My memory, though, is awful and no matter how much I wanted this to be true I couldn’t confirm it so we kept climbing upwards. We were looking for footprints or survey stations (little rock cairns) as evidence but the spring snowmelt had scoured the cave clean. Then, we spotted it: a rope in the distance from a previous climb that I’d installed years earlier and just below it was a survey marker. We’d done it: the connection between the Hirlatzhöhle and WUG Pot had been confirmed and this was now officially the deepest cave ever explored by a British Team and the 9th deepest in the world. The 50 year goal of the project had been achieved and my personal twenty year obsession was finally vindicated.”

Editorial in the British Caving Association newsletter by David Rose, editor, caver and journalist

British Caving Association Newsletter:

Hirlatzhöhle – W.U.G. Pot link breaks British expedition depth record

Most cave exploration requires persistence, whether it’s applied through digging, shaft-bashing or diving. But in the entire history of the sport there have been few, if any, efforts as long or as determined as the Dachstein project, led by Joel Corrigan on trips every year (and sometimes twice a year) for 20 years, and carried on for more than two decades before that by earlier generations of mainly British cavers. On 6th September 2018, this long siege reached a very significant milestone when Joel, Tom Foord, Ian Holmes and Axel Hack connected the far end of Wot U Got Pot to the mighty Hirlatzhöhle, so creating a system 1,560 metres deep (ninth deepest in the world) and 113 kilometres long. This beats the previous depth record for caves pushed by British expeditions by almost 300 metres.

Aftermath

I’ve spent a long, long time both above and below the Austrian Alps and even after all we’ve achieved, I’m still struck with awe when I think about the mysteries that lie in wait beneath us. It truly is a stunning environment and the austere beauty of the surface is magnified below the earth. So yes, we’ve reached our primary goal, but it has now highlighted the true potential of the region: millions of years ago the cave system ran from one side of the mountain range to the other and discovering the missing miles will give us a depth of approximately 2.2 km and a length in excess of 500 km. This would catapult our insignificant little hole into the record books and allow me to sell all my equipment and make a fortune as an after-dinner speaker!

I’m still running the project but after what will soon be twenty two years at the helm I feel as if I need to find a replacement. Typically, each summer we have about forty people from all over the world and quite a few of those are brand new to caving: experience isn’t a necessity as we’re past-masters at training people to stay alive in the underworld. I’m not sure if the Caving and Climbing Club is still in existence but if any Old Stoics want to get involved then feel free to get in touch. If anyone needs the service of a company specialising in difficult access both above and below ground then drop me a line. www.unlimitedaccess.co.uk

Joel Corrigan (Lyttelton 87)