Stowe can claim to have been a seat of learning and education long before the School opened in 1923. In the 18th century, Lord Cobham educated his band of nephews in the arts of politics and gardening, while Alexander Pope translated Horace’s Latin poems during his visits. Earl Temple took music lessons from Rawlins and tried architecture with Borra.

Perhaps the person who made greatest use of what he learnt at Stowe was Capability Brown. He arrived in 1741 aged about 25. He was already a practised gardener and water engineer. He quickly assumed the role of clerk of works, not just managing the gardeners and planning Lord Cobham’s new works, but also supervising masons involved on the numerous building projects.

Brown worked hard from his home in the West Boycott Pavilion and soon turned his hand to architecture too. During his ten years at Stowe, he doubtless learnt much from James Gibbs, who designed the Temple of Friendship and the Gothic Temple in 1739 and 1741. Gibbs had published designs in A Book of Architecture of 1728 so that others could copy best practice. At this time, he was the only leading British architect who had trained professionally in Rome. Brown started by learning architectural terms as he copied them out from the Builder’s Dictionary or Gentleman’s and Architect’s Companion.

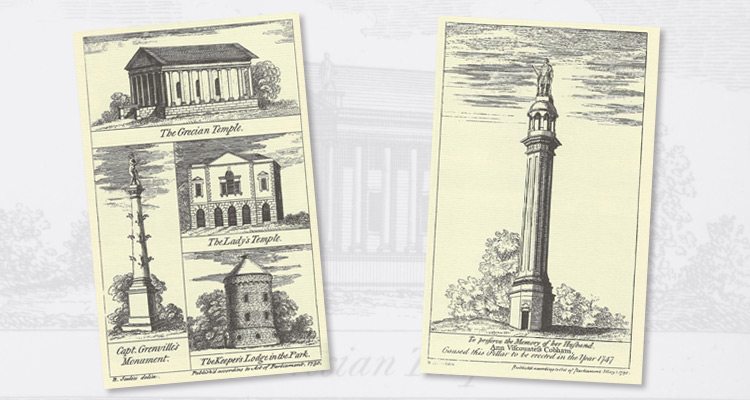

Brown soon moved into supervising his own building projects. Perhaps his first was in about 1742 for the Lady’s Temple, now the Queen’s Temple. He adapted this from Gibbs’ engraving in A Book of Architecture (plate 68) of his 1720 design for the Bowling Green House at Down House. This was intended for the poet and diplomat Matthew Prior but he died before he could build it.

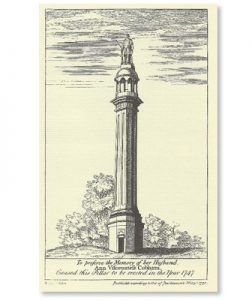

Then came Lady Cobham’s tall pillar in honour of her husband. Brown built this in 1747 following Gibbs’ plan but he added eight large flutes which, he said, were “to make it more monumental and to answer the octagonal form of ye Pillar.” This change was ‘not admired’ and had not been ‘authorised’, according to Earl Temple, but Brown was always persuasive in dealing with his clients.

Then came Lady Cobham’s tall pillar in honour of her husband. Brown built this in 1747 following Gibbs’ plan but he added eight large flutes which, he said, were “to make it more monumental and to answer the octagonal form of ye Pillar.” This change was ‘not admired’ and had not been ‘authorised’, according to Earl Temple, but Brown was always persuasive in dealing with his clients.

Brown’s greatest architectural triumph in Stowe’s garden (he also worked on Stowe House) was the Grecian Temple, also of 1747. Now the Temple of Concord and Victory, it was the focal point of his new Grecian Valley, with Lord Cobham’s Pillar visible along the Grecian Diagonal. This time Brown copied ‘in part’ the Temple of Bacchus at Baalbek, as Pococke later confirmed, probably from engravings in Pococke’s book of 1745.

It was innovative, as the first Grecian Temple in England based on extant classical remains. Vanbrugh’s earlier Rotondo in the Hellenistic style had been based on written descriptions only. Brown was not a purist in his approach: his narrow flight of steps and the three arched windows on each side were all removed under the later refinements of Borra, who had himself just visited Baalbek. Borra also removed the fireplace at the west end; Brown was more practical, preferring heat and light to classical gloom and cold.

Nevertheless, Brown’s Grecian Temple was a triumph. It was Britain’s first fully peripteral building in a hexastyle temple plan since Roman times. It was also the making of Brown as an architect, since this Temple at Stowe “raised him into some degree of estimate as an architect” (Morning Post, 30 July 1774). His architectural education at Stowe stood him in good stead for his later successes at Croome Court, Burghley and Corsham, among many others.

Michael Bevington, Stowe Archivist