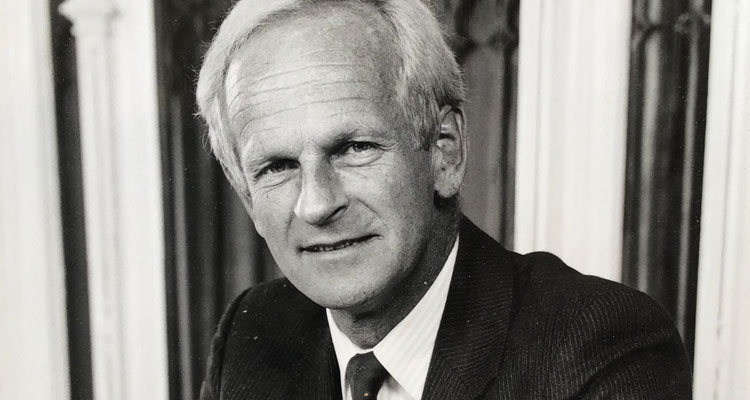

20 May 1943 – 8 August 2020

Jeremy Nichols treated pupils in his charge like grown-ups, both at Eton, where he taught English and became a Housemaster, and at Stowe, where he was Headmaster for 14 years.

Jeremy Nichols treated pupils in his charge like grown-ups, both at Eton, where he taught English and became a Housemaster, and at Stowe, where he was Headmaster for 14 years.

The House he inherited at Eton was in a state of flux when he took over in 1981 but he turned it around faster than anyone expected with his verve, wit, clear sense of right and wrong, and a belief that the boys mattered more than the rules. He referred to his South Lawn House as “the mighty red and blacks” (the House colours) and quickly won the boys’ loyalty and respect.

Known at Eton as Jerry, he and his wife, Annie, created a family atmosphere, inviting new boys for private suppers and introducing them from an early age to Nichols’s literary heroes, ranging from Dickens and Hardy to Dylan Thomas and Bob Dylan.

As a teacher of English, he was a stickler for correct pronunciation and proper use of language. Rubbish was always detritus; you weren’t lucky, but fortunate. To express displeasure, he would simply bark: “Silly!” and for some reason he pronounced “absurd” with a z instead of an s.

A good all-round sportsman who won a blue at Cambridge for athletics, he was put in charge of the first XI football team at Eton, beating Charterhouse in 1972 for the first time in 11 years. His 1976 and 1978 sides were undefeated all season.

Nichols had a strong Christian faith and ran Eton’s branch of Amnesty International. One lunchtime at South Lawn, the boys were surprised that there was only bread and water on the table. This, Nichols told them, was in solidarity with those who were starving in Ethiopia. In fact, he had blown the House budget for that week!

Stowe was in some difficulty when he arrived in 1989 but Nichols threw himself into the job with enthusiasm, introducing a Tutor system and presiding over the start of the restoration of the Mansion, Stowe’s grade I listed building.

“He steadied the ship by running the School in the same way he ran his House at Eton — force of personality, charm, good humour underpinned with a strong sense of values,” Anthony Wallersteiner, the current Stowe Headmaster, said.

Jeremy Gareth Lane Nichols was born in 1943 in Walton-on-Thames, Surrey. He was the son of Derek Nichols, who flew Spitfires and Hurricanes in the war and went on to become a director of a building business, and Ruth Madge, who was known to everyone as “Muzzy”.

His parents divorced when he was eight and he had little dealings with his father. He went to Lancing College but his father stopped paying the fees when he was 16, so his godfathers and a group of family friends clubbed together to get him through his final years of education. A highlight of his first few weeks at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, was to put half his term’s grant on a single horse running at Newmarket. It came last.

While at Cambridge he became a disciple of the literary critic FR Leavis, who wrote The Great Tradition, and developed his love for the written and spoken word, as well as cars.

On the games fields, no one came close to him in the 110 yards hurdles and he played tennis, golf, cricket and football to a high standard.

“His looks, personality and sporting prowess, helped by driving around in his racing green Bentley, made him the most glamorous undergraduate of our year,” a Cambridge contemporary said.

After graduating in 1966 he spent a year teaching at Rugby before becoming a founding member of Eton’s new English department. Asked what made a good teacher, Nichols once said: “Empathy, forgiveness, demand, rigour, understanding, adaptability.”

His mantra about approaching English texts was: “This is what I like and this is why I like it. What do you think about it?” He encouraged debate and an appreciation for the arts, directing several plays, and believed that individuality and eccentricity were to be celebrated.

He met Annie Swanton, a nurse and daughter of Commander Alan Swanton, in 1971 and they married a year later. While courting, he would often leave his Eton tutorial group a note saying he had gone to London for the evening and that they should listen to Dylan Thomas on his gramophone. This they did, while enjoying his whisky and smoking with abandon because Nichols himself was a pipe smoker.

He was never without a dog, all of which were named after a Dickens character that began with a B, hence Mr Boffin, Betsey Trotwood, Barnaby Rudge.

His 1924 red label Bentley was called “the queen of the road” and when he eventually sold it to a private buyer he did so with the proviso that he could borrow it for his daughters’ weddings. He and Annie had four children: Lucy, a speech therapist; Rupert, a trading director for online retail; Victoria, a primary school teacher; and Emma, who teaches art.

At Stowe he invited pupils to breakfast if they shared his birthday, and after Chapel on a Sunday he would ask all those who had turned 18 that week to join him for drinks.

Towards the end of his tenure at Stowe he developed cardiac problems, culminating in a heart attack on the day he and his family were due to move out of the Headmaster’s lodgings. He recovered and set about retirement with typical flair.

He and Annie moved to their house near Truro, Cornwall, but also spent time at their seaside cottage in Bucks Mills, north Devon, and he became a governor of many schools. They had nine grandchildren and planted a tree to commemorate all of their births.

Annie died of cancer in 2009 aged 65, sending Nichols into what he called a “deep gloom”. He then met Katherine Lambert, an academic and former editor of the Good Gardens Guide, who he said had “made him whole again”. They set up the Literary Lunch Club in Truro and were married in 2013.

Nichols had another heart attack last year and in July he was admitted to hospital again. While there, one of his children, against medical orders, smuggled in a bottle of Mâcon, which Nichols, who enjoyed his wine, thought was so good that he should share it with his doctors even if it blew his cover.

Jeremy Nichols, headmaster, was born on May 20, 1943. He died of heart failure on August 8, 2020, aged 77

Mark Palmer, Independent Newspapers Professional and Old Etonian