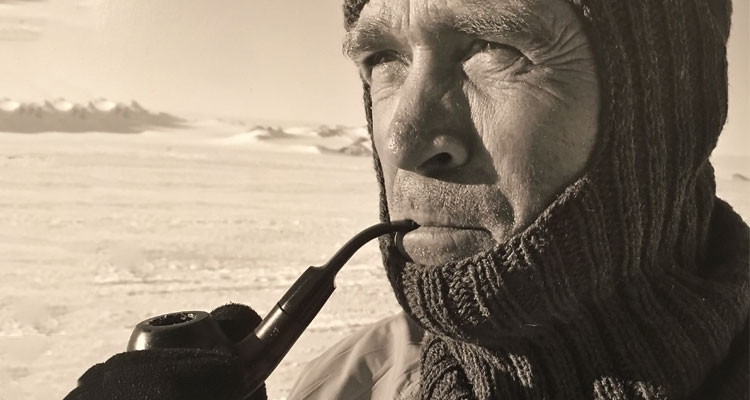

Henry Worsley: in memory of the heroic Antarctic explorer, who died doing what he loved

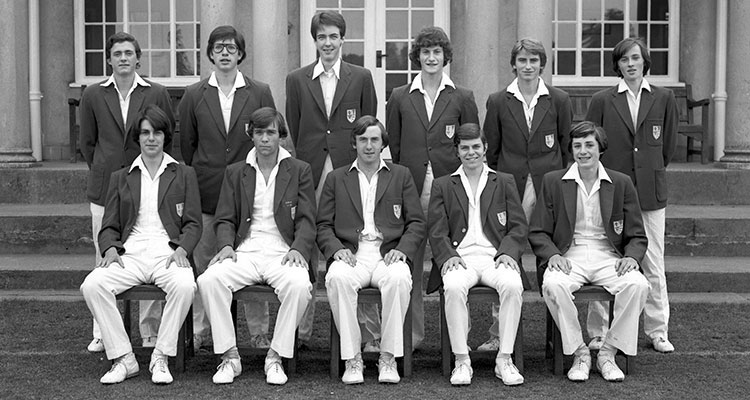

OS Explorer, Lt Col Henry Worsley (Grafton 78), died on 24 January 2016, after an heroic expedition to cross the Antarctic, solo and unaided. We were following his expedition from the Old Stoic Office with the intention of featuring him in this edition of The Corinthian. We were devastated to hear of his death and we are dedicating this year’s cover story to him to pay tribute to his memory and achievements. Henry’s adventures set an example to all Old Stoics: to push to achieve your goals and live life to the full.

Stefano Hatfield, Henry’s former brother-in-law, remembers a man with a strong sense of honour and duty.

There is an old Italian proverb which says: “It’s better to live one day as a lion than a lifetime as a sheep.” Henry Worsley, the brave British explorer who died after ending his attempt to cross the Antarctic unaided and unassisted, went better than that: he lived his entire life as a lion.

Henry actually lived more lives than most of us could ever dream. It was typical of his larger than life personality and huge generosity of spirit that this former Lieutenant Colonel perished raising money for the Endeavour Fund in aid of severely wounded veterans (Prince William and Prince Harry are supporters).

He had raised more than his target total of £100,000, a target for a cause more important to Henry than the crossing itself. But, in the last (day 70) of the daily (mesmerising) radio broadcasts from his trek, he talked of how he had “shot his bolt” like his hero Sir Ernest Shackleton. He added that he needed to “lick his wounds” and reconcile himself to the fact that he would have to call for assistance after 70 days and almost 1,000 miles, just 30 miles short of his final destination.

Henry was distantly related to a member of the original Shackleton team, and admired the great explorer, at least as much for the fact that he put the safety of his men ahead of the success of his expedition and his own life, as for the Polar trek itself. He also admired Shackleton’s rivals, Robert Scott and Roald Amundsen.

He had the bug. This was Henry’s third Antarctic trek since taking up exploring in his late 40s. He had reached the South Pole twice before: in 2008/9, recreating Shackleton’s Nimrod journey, and in 2012, leading a team of soldiers in a race along Amundsen’s route.

This time, he was adamant: he would go unassisted and unaided – no kite or dogs to help drag his sleigh across the ice, and no resupply. Just a driven man battling the elements and his own frailties in a landscape he absolutely adored.

We last talked the week before he left, when he humoured my incredulous questions about the physical and mental strength that such an endeavour would necessitate. With typical understatement, he insisted that it didn’t take much to simply slide one ski in front of another (for 913 statute miles in temperatures of up to -40C!), but that it was all about the mental challenge.

He also talked me through his military career in a way he had never before in the 20 years I knew him. Lt Col Henry Worsley (MBE) had encompassed being Commanding Officer of the 2nd Battalion, The Royal Green Jackets, and senior roles within the SAS in locations such as Afghanistan (twice), the Balkans and Northern Ireland.

Henry was the essence of what one believes to be the best of the British Armed Forces: loyal to, and fiercely protective and proud of, his country and his fellow soldiers. He was action-man brave – obviously – but unwaveringly cool and decisive under pressure. In short, both a team player and a genuine leader of men. That said, there was so much more to him than the army and exploring.

Although he would deprecate his own abilities, he was a keen painter and became pretty competent at needlepoint, taking it up in the unlikely surroundings of the Balkans conflict out of sheer boredom. So, although Henry could lecture about exploring at the Royal Geographical Society, he would also give talks to prisoners about needlepoint. It somehow sounded different coming from someone like him, as did the fact he kept ferrets for a while.

If the army formed him – both his father and grandfather were also highly distinguished soldiers – then his family completed him. And, although forced to be away from his wife Joanna, son Max and daughter Alicia for long periods of time, he took an immense pride in his family, which extended beyond the immediate.

In some ways he felt like a man out of his time, so strong was his sense of valour, duty, ethics and simply “doing the right thing” in an unmistakably British way – in an era where even to say this appears sadly unfashionable.

In summary, he was a man of many and varied talents, some expected, others less so. But more than anything he was that rarest of things: a man of honour and self-evident integrity; the sort of person who makes you proud to know him, who makes you want to be better yourself.

Henry Worsley, a truly special man, leaves a wife Joanna, son Max, daughter Alicia, mother Sally and sister Charlotte.

Stefano Hatfield

Postscript: Henry was awarded a Polar medal in the New Year’s Honours list 2017, making him the first person to receive the medal posthumously since Shackleton.