8 March 1931 – 6 April 2022

Discretion was Richard Cox’s middle name. It was not until he was on a family holiday in Kenya’s Aberdare National Park in 1982, just after the failed coup, that he mentioned that the last time he had signed the visitors’ book at Treetops Lodge he was awaiting execution. Working as a Sunday Times foreign correspondent during the Mau Mau uprising 30 years earlier, he had strayed with a US journalist into dangerous territory and was captured and held at the lodge. On the morning of the execution he was told that the US government had intervened to ensure their release.

Despite the incident, Kenya was a country that Richard returned to for much of his life, but it was a bumpy relationship. In 1964 he upset the newly independent government and was given 24 hours to leave but was forgiven a year later after publishing his positive account of the country’s transition to independence in Kenyatta’s Country. In the same year he also published the well-received Pan-Africanism in Practice.

For Richard, writing was his lifeblood and a talent that he tapped into for his varying professional roles as a journalist, author and speechwriter. His lasting regret was that he never became a playwright.

In the early 1970s he saw a gap in the market for concisely written paperback guidebooks and set up a publishing company, Thornton Cox. Its guides to Europe, Africa and the Caribbean remained in publication for some 30 years and at his sons’ prep school were pronounced obligatory night-time reading by an idiosyncratic Headmistress, keen for her pupils to learn about the world.

The success of the guidebooks prompted Richard to deliver in 1974 his first novel, Operation Sealion, a fictional account of Hitler’s planned invasion of Britain in 1940. Over the next 30-odd years he would publish 12 more novels, some of which became bestsellers. Sam 7, about an Arab terrorist shooting down an airliner over London, was serialised in the Evening Standard and made compulsory reading for the capital’s emergency services. With the profits from the book Richard bought a house in Earls Court, London, which he later swapped for Flood Street, Chelsea.

Yet perhaps the most enjoyable period of his life was as a speechwriter, a role he undertook in the aftermath of the Falklands conflict for Admiral Sandy Woodward, the Task Force commander, as well as for the Aga Khan, which meant travelling the world with him during his silver jubilee year in 1982.

Later in the decade he was also a founding board director of Care Britain and was involved in famine relief on the Kenyan and Somalian border.

Richard Cox was born in Winchester, Hampshire, in 1931. His Australian-born father, Eustace, had worked for the Indian railways before arriving in England and marrying Joan (née Thornton), an ambulance driver in the First World War.

When Richard was two, his father deserted mother and toddler after leaving £25 on the hall table. Richard did not see him again until he tracked him down at 18 – only for his father to slam the door in his face. His mother had a series of nervous breakdowns that led to her spending much of her life in nursing homes while Richard was passed round relatives during school holidays. When he was 16 he ran away from one family to join a travelling theatre company for the summer.

At Stowe, Richard was academically overlooked and discouraged from applying to Oxford. After National Service he took the application into his own hands and got into St Catherine’s College on a county scholarship to study English. He became president of the Oxford University Dramatic Society and took it to the 1952 Berlin Festival with Twelfth Night. At Oxford he also signed up to the university’s air squadron, audaciously using a training aircraft to drop flyers of forthcoming plays over Cambridge.

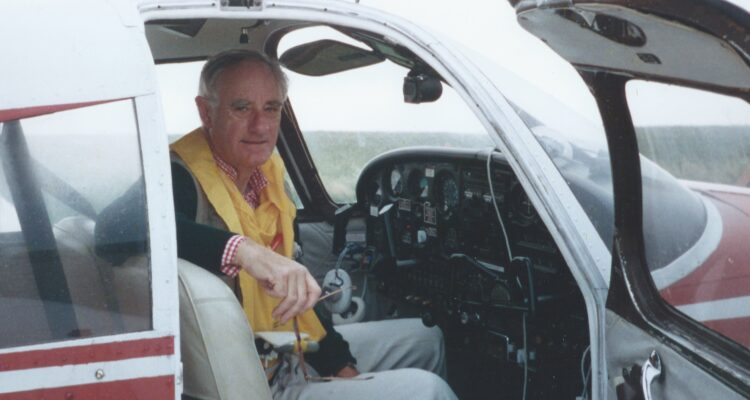

Piloting a plane turned into a hobby that he pursued for much of the rest of his life, often to the dismay of others. In 1964 he borrowed a friend’s aircraft to report on the Zanzibar revolution without telling him where he was heading. He was again imprisoned and put under sentence of death until a journalist’s intervention saved him. His second wife, Francesca, had to tolerate his sudden packing up of the house — newspapers and milk cancelled — while he took off without knowing where, or telling her.

After university, Richard had a spell as a trainee at the Bristol Aeroplane Company followed by a desk job with the Foreign Office. In 1960 he left it to become a foreign correspondent for The Sunday Times, covering conflicts in Africa, India and Lebanon while basing himself in Nairobi.

Returning to Britain in 1964, he went back to the Foreign Office as a first secretary and subsequently got a job as defence correspondent for The Daily Telegraph. He was also with the Territorial Army, including 18 years with the 44th Independent Parachute Brigade. With the Telegraph he was posted to Aden as a TA officer leading up to the withdrawal in 1967, for which he received a campaign medal.

In 1962, Richard married Caroline Jennings, whom he met at a party in Britain and she followed him out to Kenya and found a job writing for Nairobi’s Daily Nation. The marriage lasted six years and in that time they had three children: Lorna, formerly a financial journalist in New York; Ralph, a solicitor; and Jeremy, a doctor. In 1983 he married Francesca Noad, whom he met in Kenya and they divorced nine years later.

In Richard’s later years he divided his time between Alderney in the Channel Islands and Nairobi, enjoying the social life of both and serving as a member of the States of Alderney (in the 1960s he had been a Conservative councillor in Chelsea).

In his eighties, a desire to know more of his family history prompted him to do an MPhil on the social history of New South Wales in the Victorian era (an ancestor William Cox was an early pioneer in Australia) at King’s College London. His thesis was rewritten as a biography of his ancestor in 2012 and led to a promotional tour in Australia.

An ability to tell amusing stories ensured Richard was a popular dinner guest and yet for all his exploits he presented a self-effacing manner and sometimes struggled with his own company. He enjoyed being with his children and remained close to his mother. In his late seventies he moved to Coombe Bissett, Wiltshire, just a mile or so from where he had spent happy times with her in his early childhood.

Obituary from The Times