A Stowe education has always comprised far more than the ability to disgorge knowledge in the heat of the exam season. Schools should never be just exam factories. Instead, they should educate pupils to face up to the biggest challenge of all: how to flourish as individuals by becoming the best versions of themselves. This should enable them to choose the right course of action in difficult situations, form positive relationships, contribute to the common good, acquire absolute values and know the difference between right and wrong, good and bad.

Success depends on more than what Stoics know – it depends on character, resilience, determination, adaptability, creativity and a sound moral compass. Aristotle said that the aim of study is not just to know what virtue is, but to become good. Schools should distil the wisdom of previous generations, equipping pupils with languages, scientific knowledge, numeracy and literacy. But schools should also shape character so that boys and girls can make the right decisions and learn to act virtuously in this morally relativist world.

And what are these virtues?

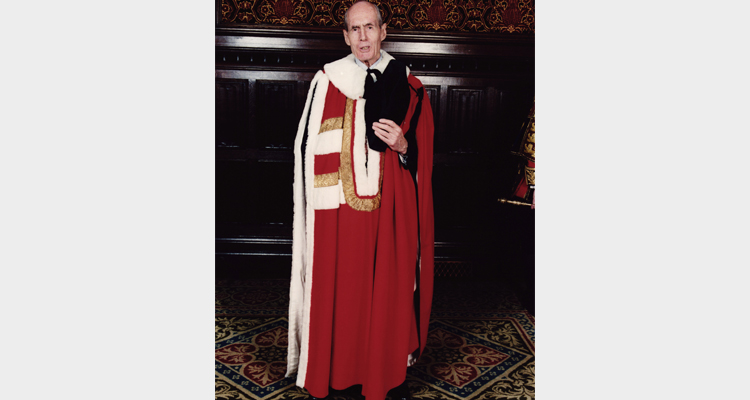

Rarely will all these character traits align, but occasionally the virtues cohere to form an exemplary Stoic like Group Capt the Lord Cheshire of Woodhall, VC, OM, DSO, DFC (Chatham 36) whose centenary we celebrate this academic year (he was born on 7 September 1917). Cheshire won a scholarship from the Dragon and shared a study in Chatham with Jock Anderson (Chatham 36), the only other Old Stoic to have won a Victoria Cross during World War Two.

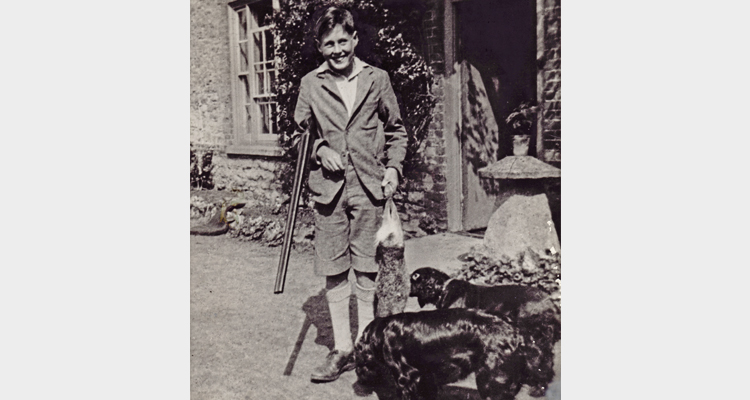

Patrick Hunter, Cheshire’s fastidious tutor and one of JF Roxburgh’s most trusted lieutenants, described Cheshire’s attitude to study as “conscientious and certainly above average, but really not remarkable.” He excelled at hockey, cross-country and tennis and rose to be Head of House and a school Prefect. Roxburgh discerned in Cheshire a “moral dignity” which “made it inconceivable that he would think or do anything that was below the top level.” Cheshire spent a term in Germany to improve his fluency of the German language. He stayed with Admiral Ludwig Von Reuter, commander of the Imperial German Navy’s High Seas Fleet which was scuttled at Scapa Flow in June 1919. Reuter later became an enthusiastic Nazi who named each of his three sons after different German warships. The young Cheshire earned a stern rebuke from the Admiral when he showed his individuality and courage by refusing to give the Hitler salute at a Nazi rally.

In 1936, Cheshire won a place at Merton College, Oxford, to read Jurisprudence. At Oxford he “learned NOT to work”, indulged his love of fast cars and modelled himself on Lesley Charteris’ raffish hero, The Saint. At one point he even held the undergraduate record for speeding from Hyde Park Corner to Magdalene Bridge in under an hour. Cheshire once returned to Stowe to visit JF and a group of curious boys gathered to admire his supercharged Alfa Romeo 1750. Eventually Cheshire emerged from the Mansion, waved goodbye to JF and sped off – but the car skidded out of control, turned over and was brought to a halt by the cricket sight-screens. The Stoics howled with derision and Cheshire had to pay £22 to repair the screens. Another famous exploit was a bet, for a pint of beer, that he could get to Paris and back with the 15 shillings of change which he had in his pocket. 14 shillings was used to get to Dieppe where Cheshire’s luck changed. He was given a lift to Paris by a former officer in the French Foreign Legion, news of the bet spread and Cheshire was asked to address the Anglo-American Press Club and, as his fame spread, he then gave a radio broadcast on his exploits. With his lecture and broadcast earnings, Cheshire travelled back first-class to Oxford to collect his winning pint.

Cheshire’s flying career began at Oxford where he discovered the Oxford University Air Squadron (OUAS). He took his first flight in February 1937 and flew three or four hours a week from Abingdon. War broke out weeks after his graduation in 1939 and Cheshire was commissioned as a Pilot Officer, volunteering for Bomber Command. He was given command of an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bomber in September 1940 and won the DSO for bringing his badly damaged and burning aircraft safely home after a raid on Cologne. A DFC was awarded in March 1941 for exceptional valour, initiative and devotion to duty. At 25, Cheshire was promoted to be the youngest ever RAF Group Captain and was given command of the bomber station at Marston Moor.

Cheshire volunteered for every mission, even when it wasn’t his turn. He knew everyone’s name, socialised with all the ranks and, when he was criticised by a senior officer for drinking in a saloon bar with non-commissioned servicemen, replied: “if I’m good enough to fight and fly with these men, I’m certainly good enough to drink with them.” He sought to improve the survival chances of airmen by making changes to aircraft design and developing new tactics.

In 1943, Cheshire dropped a rank to be given command of Guy Gibson’s legendary 617 squadron of Lancaster bombers. Cheshire refined the art of precision bombing by diving his de Havilland Mosquito to within a few hundred feet of a target and releasing flares which served as pyrotechnical guides to allow the newly developed Tallboy deep penetration bombs to be dropped from a safer altitude. When Cheshire was awarded the Victoria Cross, he had flown over 100 missions and the citation praised his bravery, careful planning and brilliant leadership over four years of fighting in the most difficult conditions. He was chosen by Churchill to be the British observer of the bombing of Nagasaki on 15 August 1945.

After his extraordinarily distinguished wartime record of service, Cheshire could have walked into any career or profession. He chose to dedicate his life outside the RAF to caring for others. At Le Court, the first Cheshire Home, he looked after Arthur Dykes, a terminally ill ex-serviceman dying of cancer. Dykes persuaded Cheshire to promise that after his death he would continue to nurse the unwanted, the helpless and the disabled. Le Court soon filled with those seeking help. Cheshire was inspirational, always finding imaginative solutions to practical and financial problems, never giving up, believing that if the cause was right, the means would somehow be found. The Cheshire movement spread to 54 countries – the first international home, Bethlehem House, opened in Mumbai on Christmas Day in 1955. Eventually there would be 270 homes, exactly the number of Old Stoics who lost their lives in combat service during the War. Cheshire’s idea was not to ask how disabled a person was but to find out what they could accomplish in spite of their disabilities. Residents were at home, not in a Home.

Cheshire married Sue Ryder on 5 April 1959 in Mumbai’s Roman Catholic Cathedral. Baroness Ryder was his equal in philanthropy as she had carried out important work to help concentration camp survivors in Poland. A prayer which they jointly composed for their wedding explained that they had found God in the sick, the unwanted and the dying and they promised to serve Him until death. Cheshire suffered from motor neurone disease and died at a Sue Ryder home in Cavendish in 1992.

At Cheshire’s memorial service in 1992, Cardinal Basil Hume praised Cheshire for welcoming God into his life with transformative results: Cheshire had said yes to God, not half-heartedly, not with reluctance, but characteristically in a manner that was total and even radical. These words were echoed by Hume’s successor, the late Cardinal Cormac Murphy O’Connor, when he spoke in Stowe Chapel in June 2017 and paid tribute to Cheshire – a man he knew well and admired greatly.

This is what Cheshire said of his time at Stowe: “I know only too well how great a debt I owe to Stowe, for the start that it gave me in life. Not only were they very happy days indeed, but I look upon myself as having been exceptionally fortunate in all my schooling. What a difference a good school can make, and how fortunate some of us are by comparison with others.”

Leonard Cheshire exemplifies all of the moral, civic and personal virtues we want to see in Stoics and Old Stoics alike and it is fitting that we celebrate his achievements in this centenary year of his birth. David Wynne’s (Grenville 44) noble statue of Cheshire stands outside Chapel with its inscription, Hero and Humanitarian. The challenge is to let this one great life be the taper which inspires a flame in each of us to serve a greater cause.

Leonard Cheshire Disability is this year’s School Charity – if you would like to make a donation please contact Emma.Pearce@leonardcheshire.org

Dr Anthony Wallersteiner, Headmaster